The 2023 Arctic Report Card has been published by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). All sorts of things are discussed in the report, but sticking to Snow White’s speciality of sea ice here’s an extract:

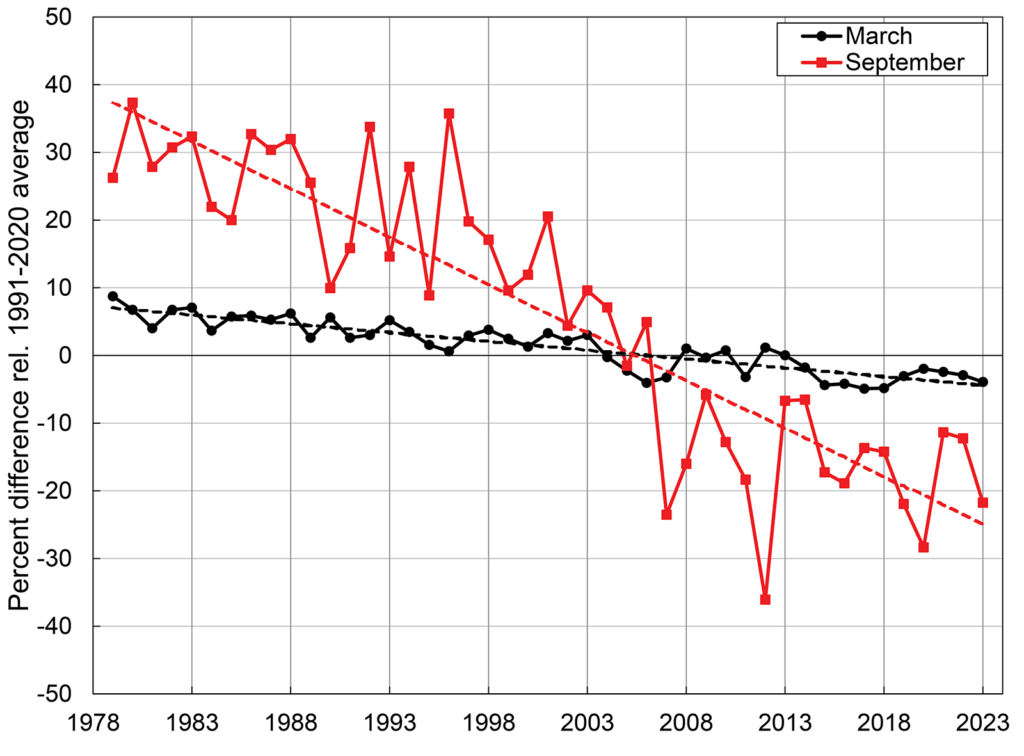

This satellite record tracks long-term trends, variability, and seasonal changes from the annual extent maximum in late February or March and the annual extent minimum in September. Extents in recent years are ~50% lower than values in the 1980s. In 2023, March and September extents were lower than other recent years, and though not a new record low, they continue the long-term downward trends:

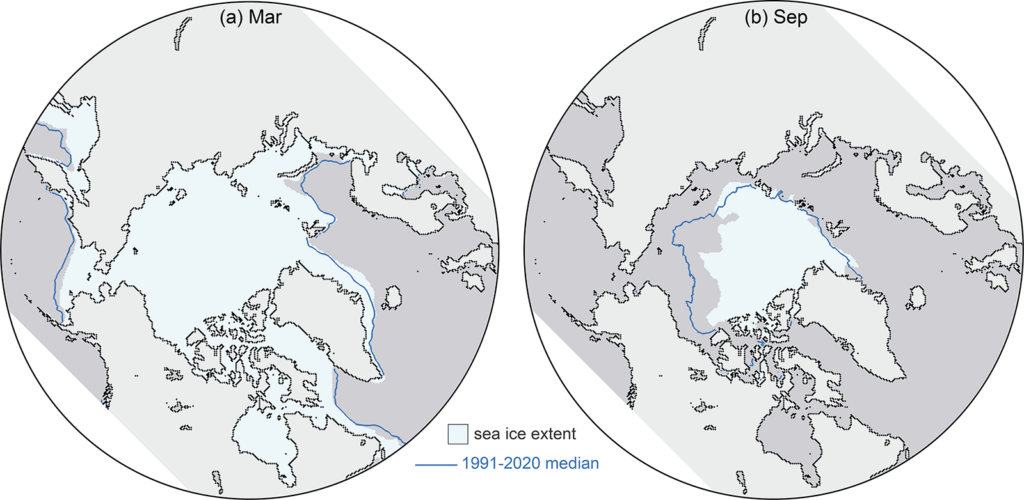

March 2023 was marked by low sea ice extent around most of the perimeter of the sea ice edge, with the exception of the East Greenland Sea where extent was near normal. At the beginning of the melt season, ice retreat was initially fairly slow through April. In May and June, retreat increased to a near-average rate, and then accelerated further through July and August. By mid-July, the ice had retreated from much of the Alaskan and eastern Siberian coast and Hudson Bay had nearly melted out completely. In August, sea ice retreat was particularly pronounced on the Pacific side, opening up vast areas of the Beaufort, Chukchi, and East Siberian Seas. Summer extent remained closer to average on the Atlantic side, in the Laptev, Kara, and Barents Seas

The Northern Sea Route, along the northern Russian coast, was relatively slow to open as sea ice extended to the coast in the eastern Kara Sea and the East Siberian Sea, but by late August, open water was found along the coast through the entire route. The Northwest Passage through the Canadian Archipelago became relatively clear of ice, though ice continued to largely block the western end of the northern route through M’Clure Strait through the melt season. Nonetheless, summer 2023 extent in the Passage was among the lowest observed in the satellite record, based on Canadian Ice Service ice charts.

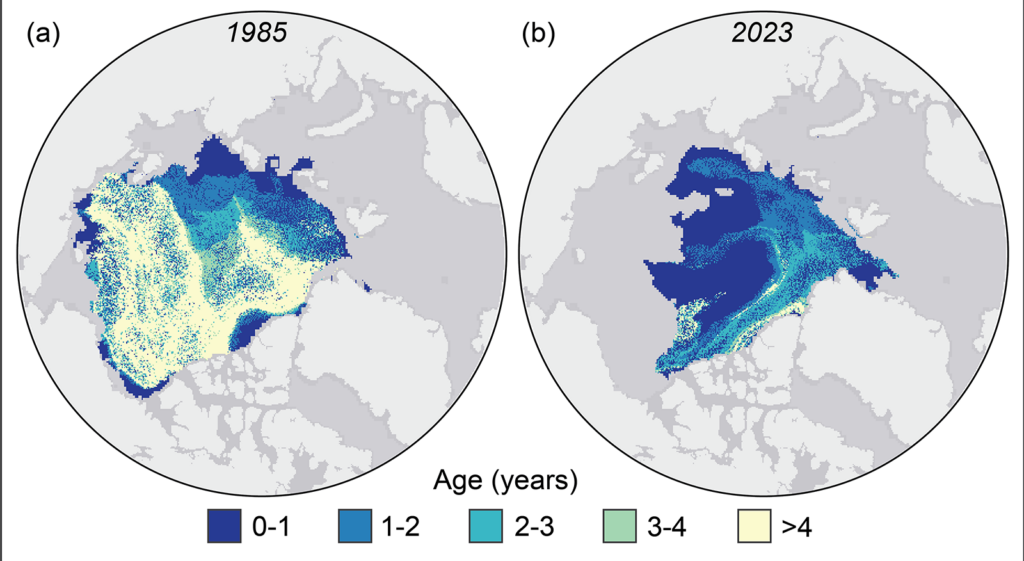

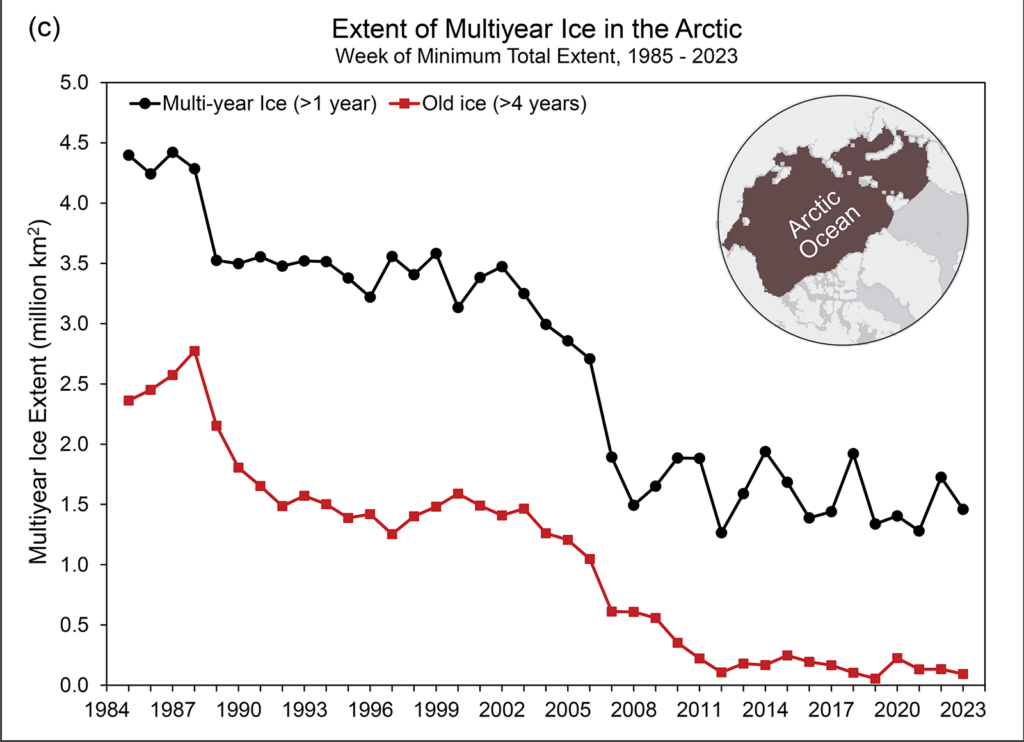

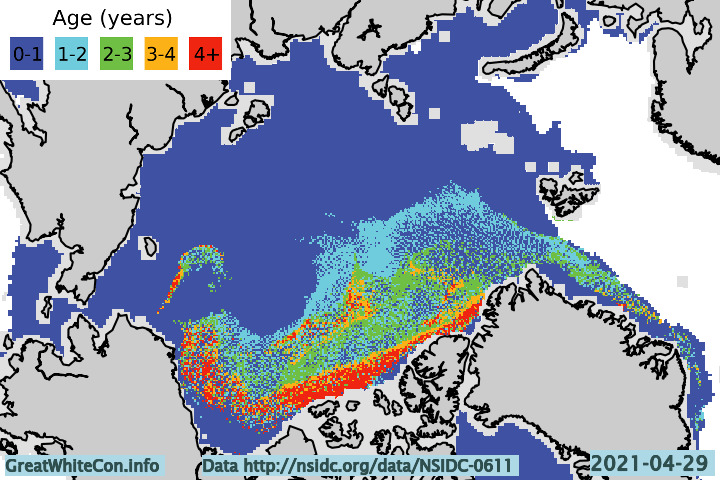

Tracking the motion of ice in passive microwave imagery using feature tracking algorithms can be used to infer sea ice age. Age is a proxy for ice thickness because multiyear ice generally grows thicker through successive winter periods. Multiyear ice extent has shown interannual oscillations but no clear trend since 2007, reflecting variability in the summer sea ice melt and export out of the Arctic. After a year when substantial multiyear ice is lost, a much larger area of first-year ice generally takes its place. Some of this first-year ice can persist through the following summer, contributing to the replenishment of the multiyear ice extent:

However, old ice (here defined as >4 years old) has remained consistently low since 2012. Thus, unlike in earlier decades, multiyear ice does not remain in the Arctic for many years. At the end of the summer 2023 melt season, multiyear ice extent was similar to 2022 values, far below multiyear extents in the 1980s and 1990s:

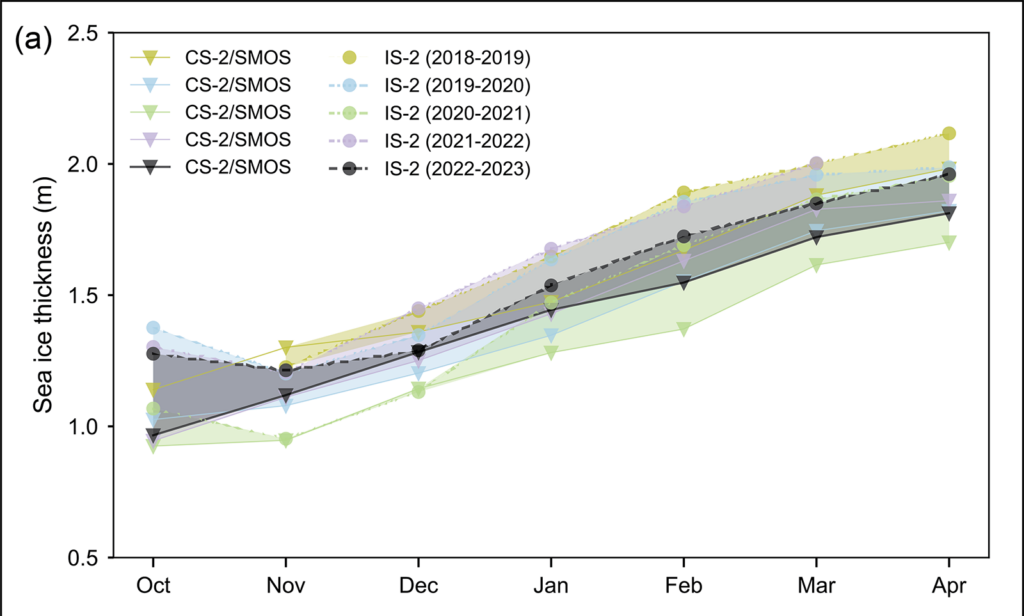

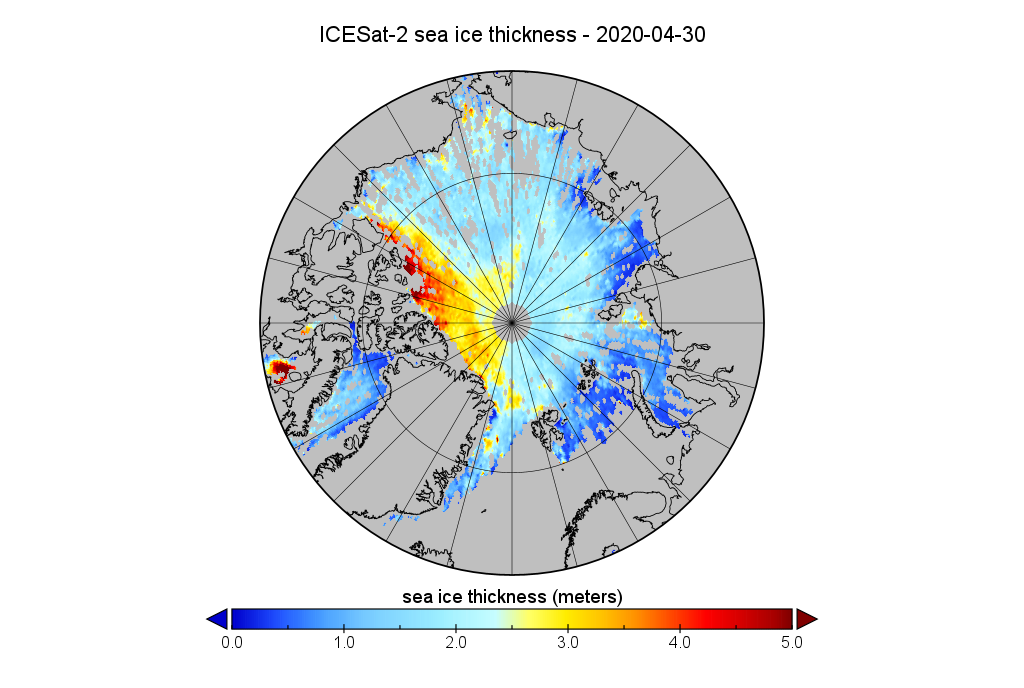

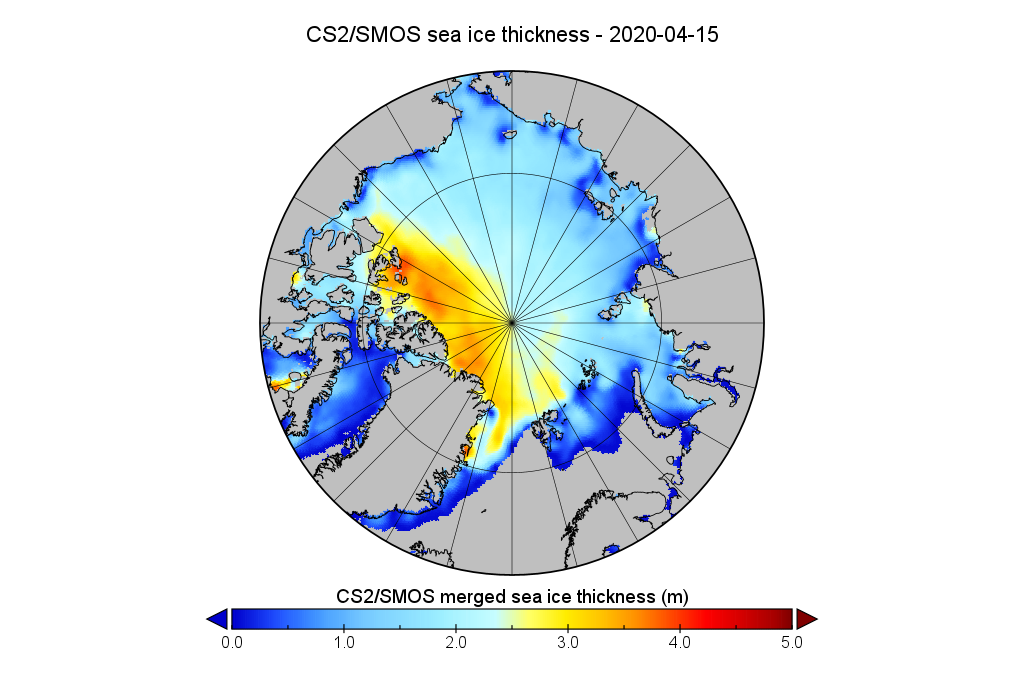

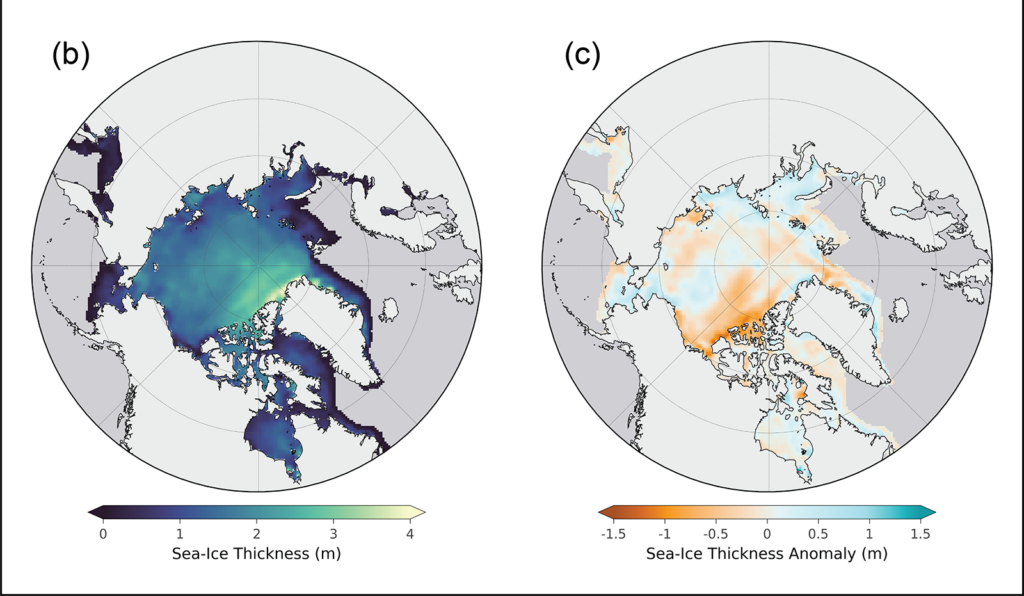

Estimates of sea ice thickness from satellite altimetry can be used to more directly track this important metric of sea ice conditions, although the data record is shorter than for extent and ice age. Data from ICESat-2 and CryoSat-2/SMOS satellite products tracking the seasonal October to April winter ice growth over the past four years (when all missions have been in operation) show a mean thickness generally thinner than the 2021/22 winter but with seasonal growth typical of recent winters:

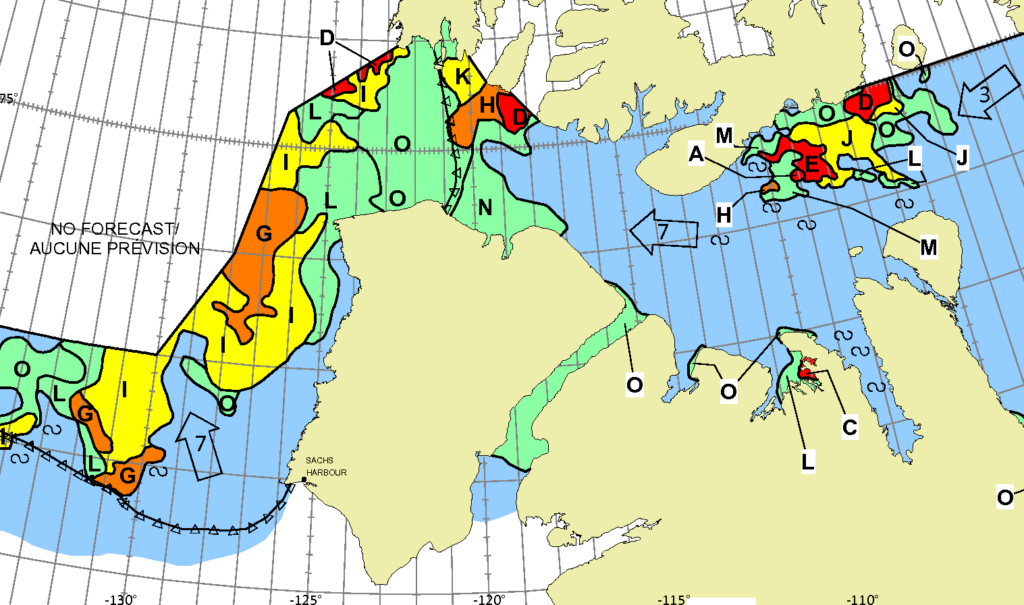

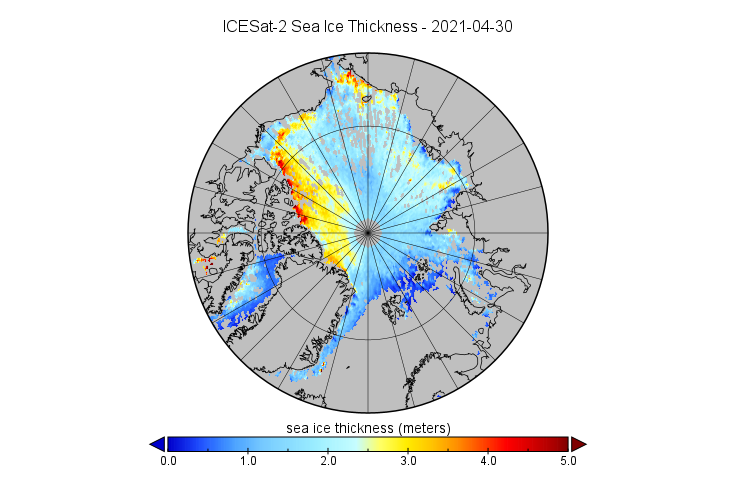

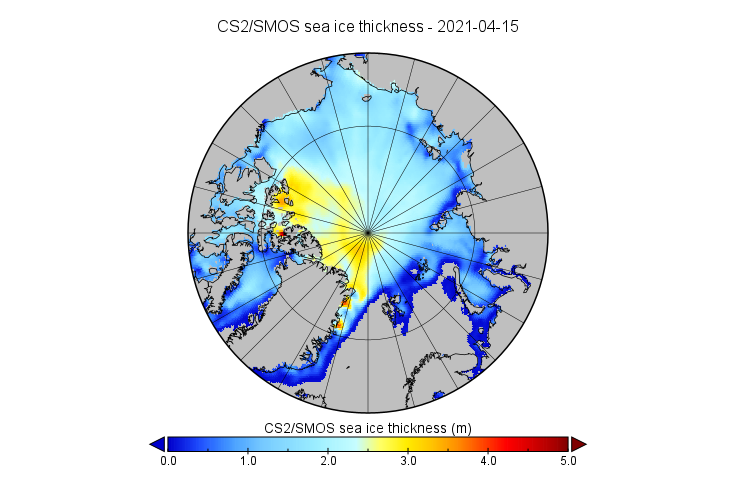

April 2023 thickness from CryoSat-2/SMOS relative to the 2011-22 April mean shows that the eastern Beaufort Sea and the East Siberian Sea had relatively thinner sea ice than the 2011-22 mean, particularly near the Canadian Archipelago. Thickness was higher than average in much of the Laptev and Kara Seas and along the west and northwest coast of Alaska, extending northward toward the pole. The East Greenland Sea had a mixture of thicker and thinner than average ice:

An excellent analysis (IMHO!), but I do have one quibble. I was following events in the Northwest Passage very closely last summer, and according to the Canadian Ice Service on September 1st: