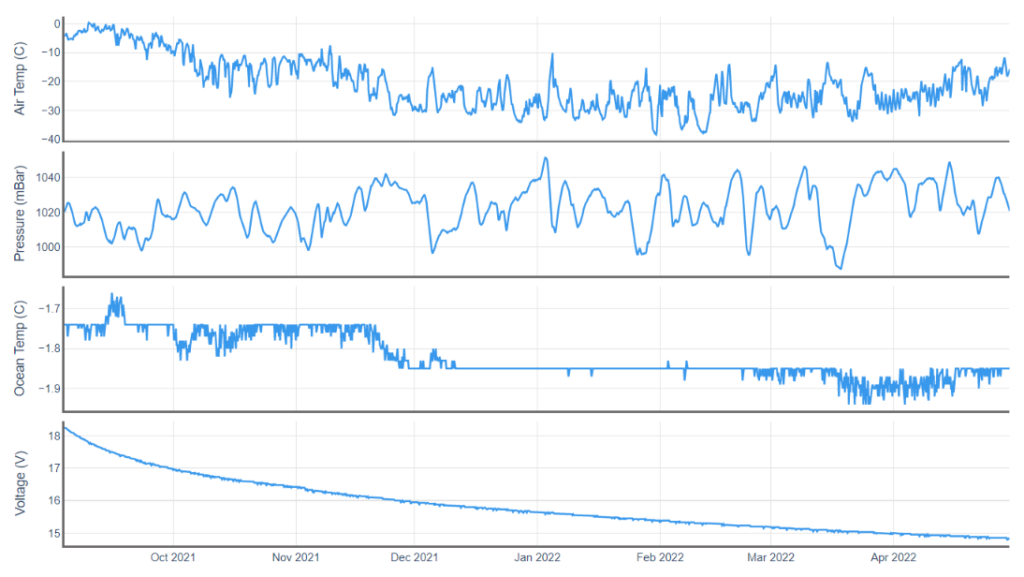

By way of a change we’ll start the month of May with a closer look at one of the ice mass balance buoys deployed in the Beaufort Sea last Autumn. IMB buoy 569620 was deployed at 78.5 N, 147.0 W on September 3rd 2021, and since then it has drifted to 81.0 N, 147.7 W. Here is the buoy’s record of atmospheric conditions above the ice floe it’s embedded in since then:

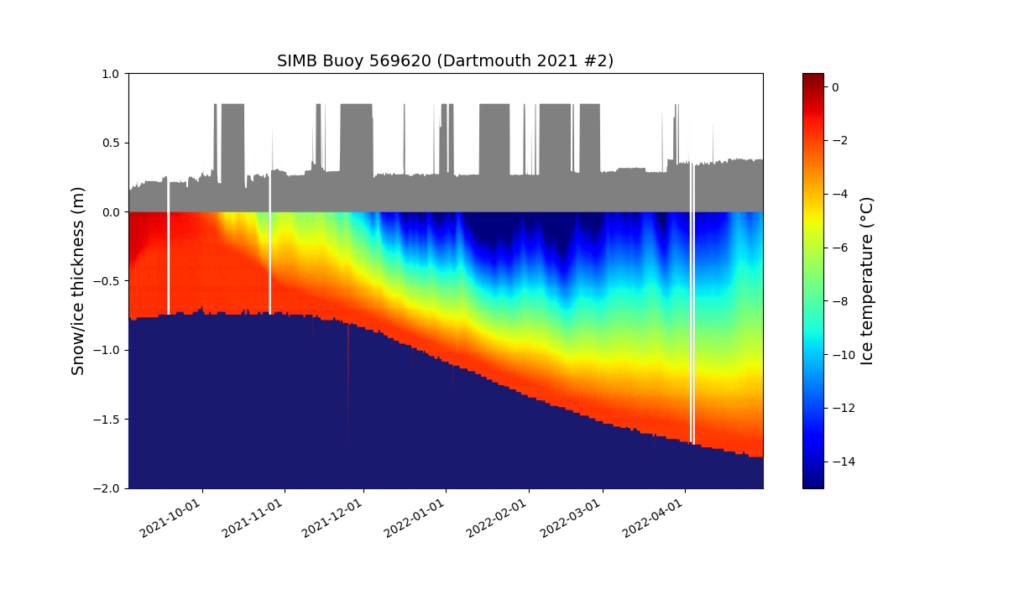

Here too is the buoy’s record of the temperature of the ice floe itself, as well as the thickness of the ice and the snow layer covering it:

There’s a few things to note at first glance. The ice floe continued to decrease in thickness into November. It’s thickness then started to increase, but is currently still less than 2 meters. Also the snow depth has gradually been increasing, and (apart from some data glitches!) is now ~38 cm. Finally, for the moment at least, the ice surface temperature has been slowly warming since mid February and is now ~-11 °C.

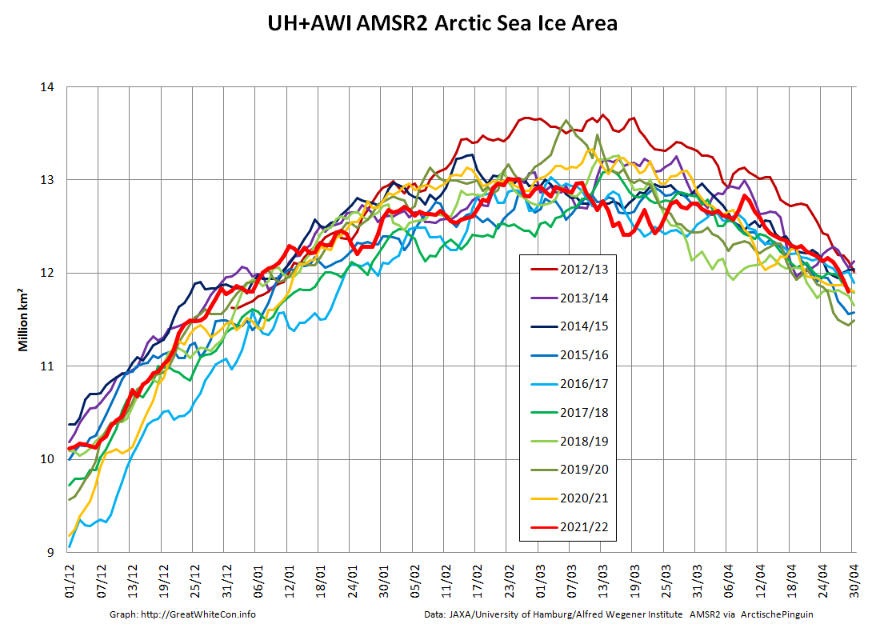

Returning to more familiar territory, high resolution AMSR2 Arctic sea ice area has taken a bit of a tumble recently:

followed less steeply by extent:

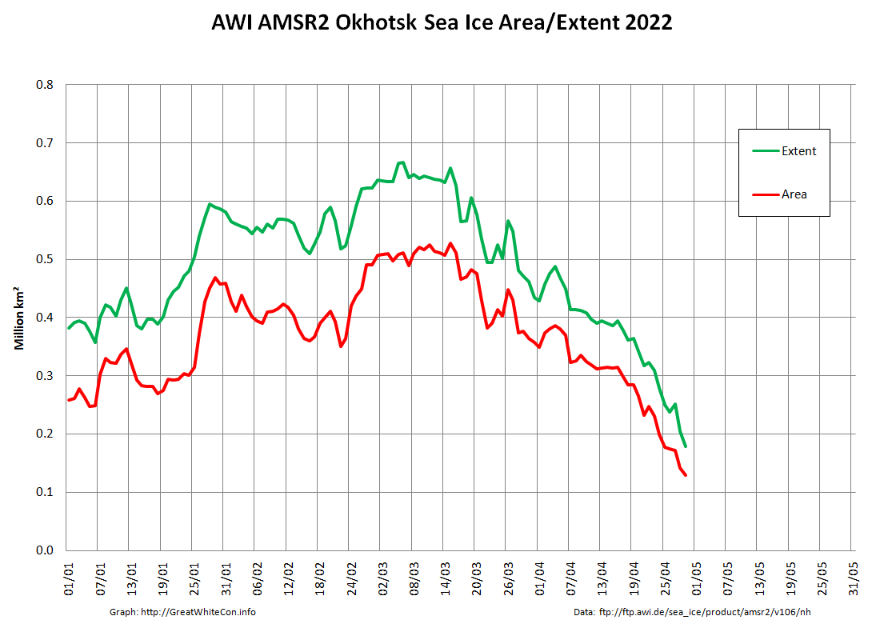

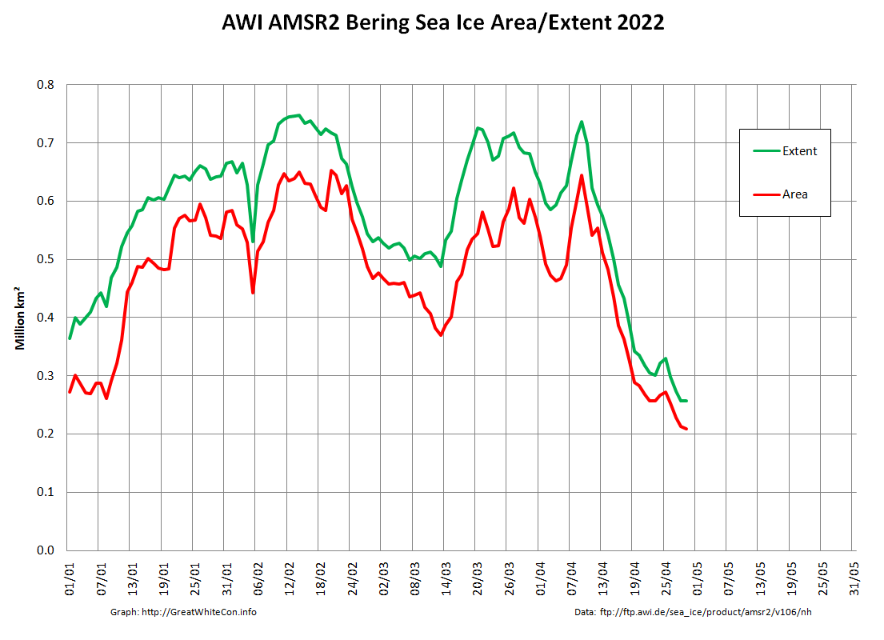

Not unexpectedly, the Pacific periphery is currently leading the decline:

The Rutgers Snow Lab has updated its northern hemisphere snow cover bar chart for April 2022:

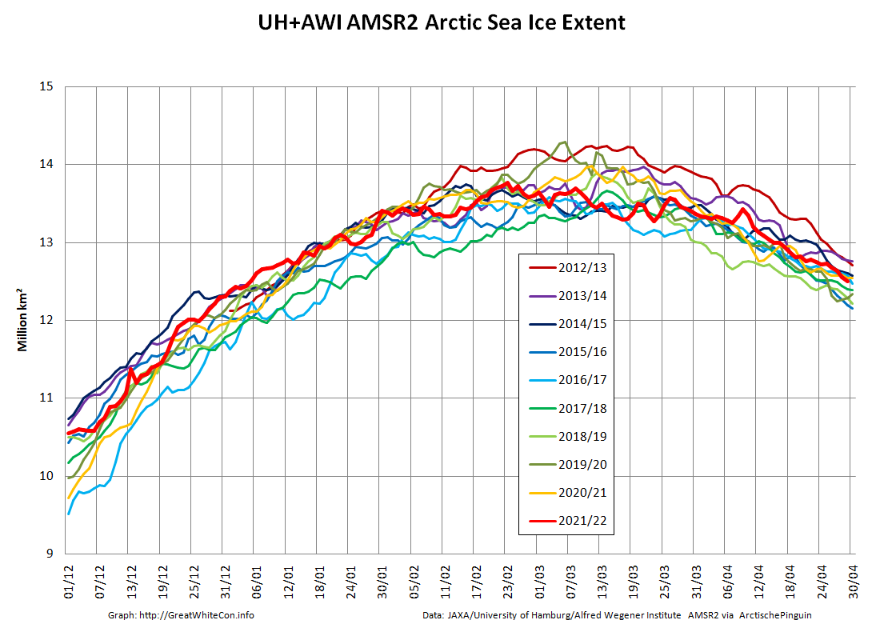

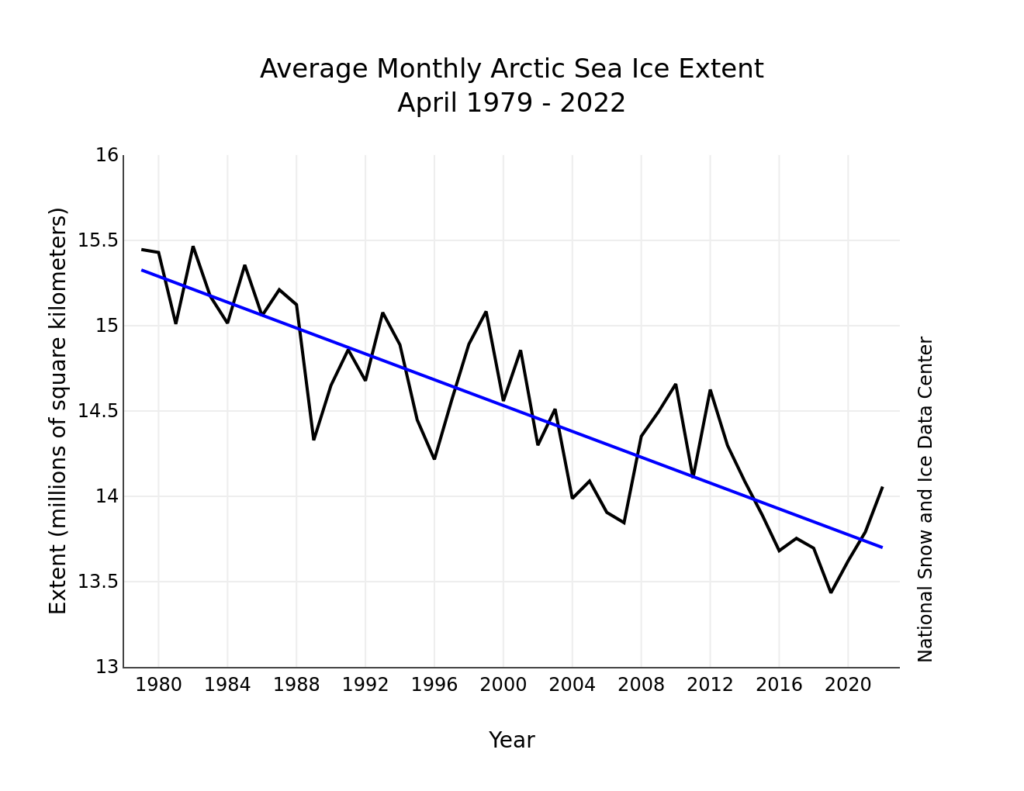

The May edition of the NSIDC’s Arctic Sea Ice News has also just been published. It summarises April 2022 as follows:

Average Arctic sea ice extent for April 2022 was 14.06 million square kilometers (5.43 million square miles). This was 630,000 square kilometers (243,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 average and ranked eleventh lowest in the 44-year satellite record.

Extent declined slowly through the beginning of the month, with only 87,000 square kilometers (33,600 square miles) of ice loss between April 1 and April 10. The decline then proceeded at an average pace for this time of year through the reminder of the month.

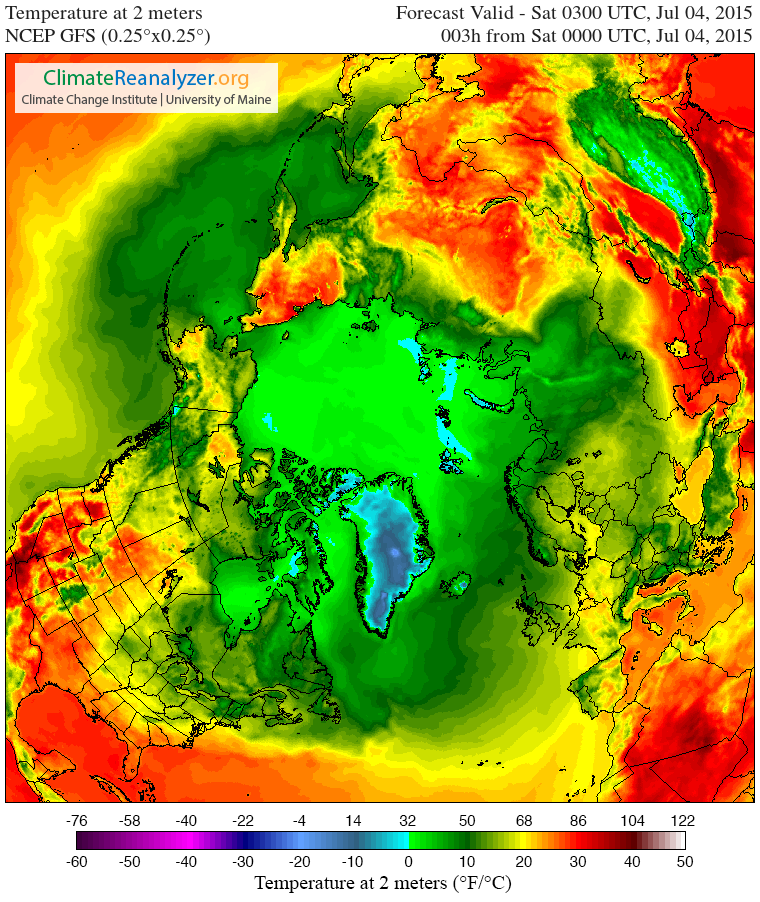

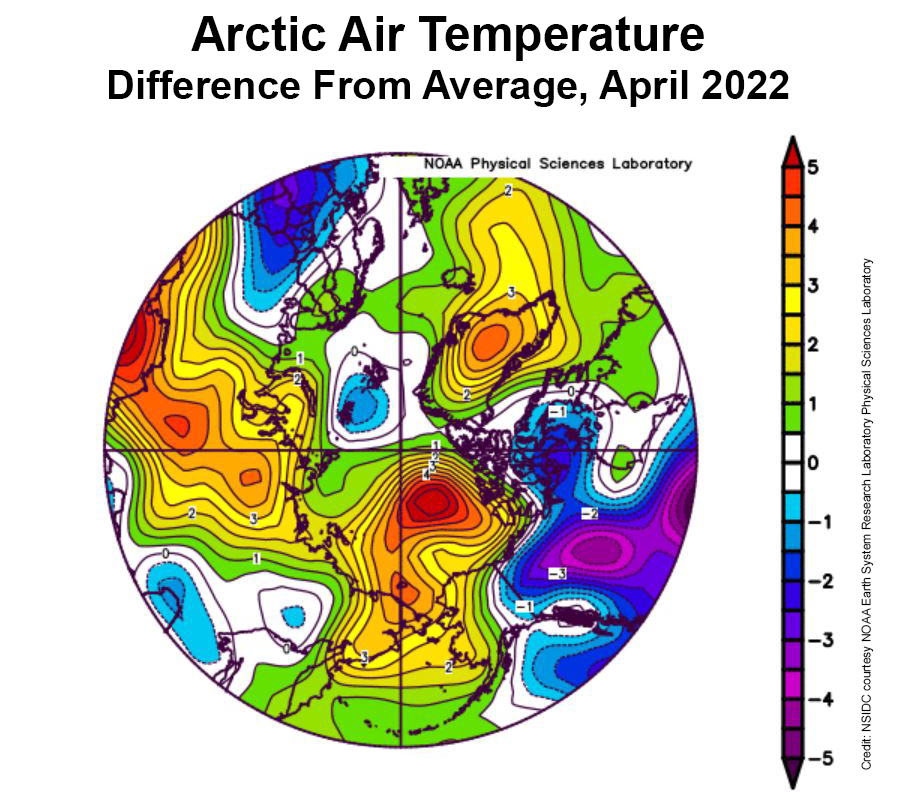

During April, temperatures at the 925 mb level (about 2,500 feet above the surface) over the Arctic Ocean were above average. Most areas were 2 to 3 degrees Celsius (4 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit) above average, but in the Beaufort Sea, April temperatures were up to 5 to 6 degrees Celsius (9 to 11 degrees Fahrenheit) above average:

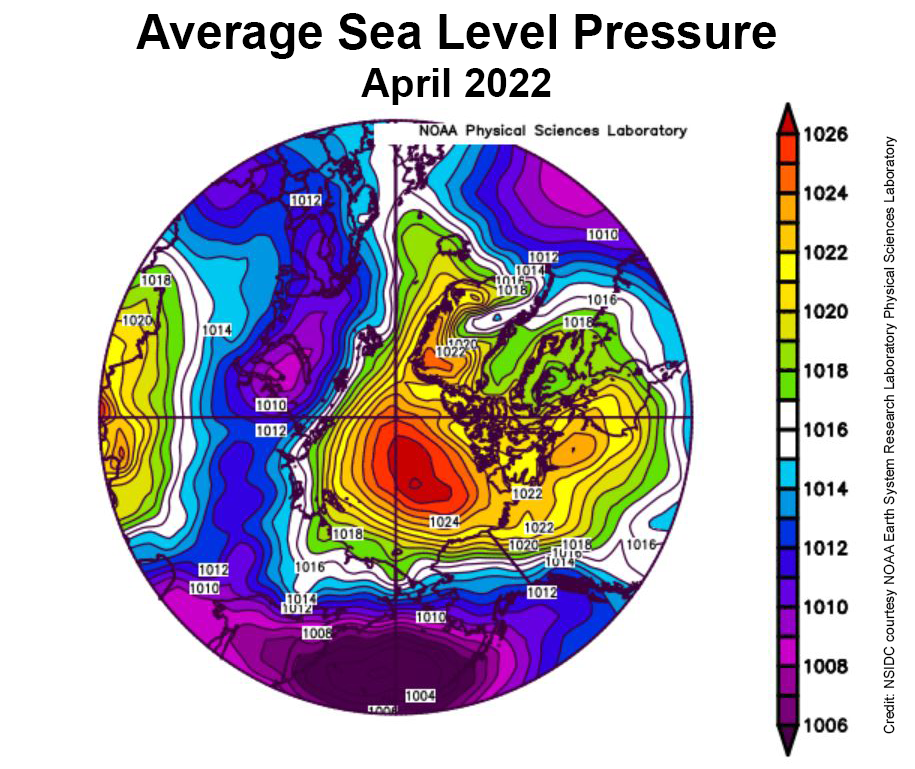

This was accompanied by a strong Beaufort High pressure cell through the month:

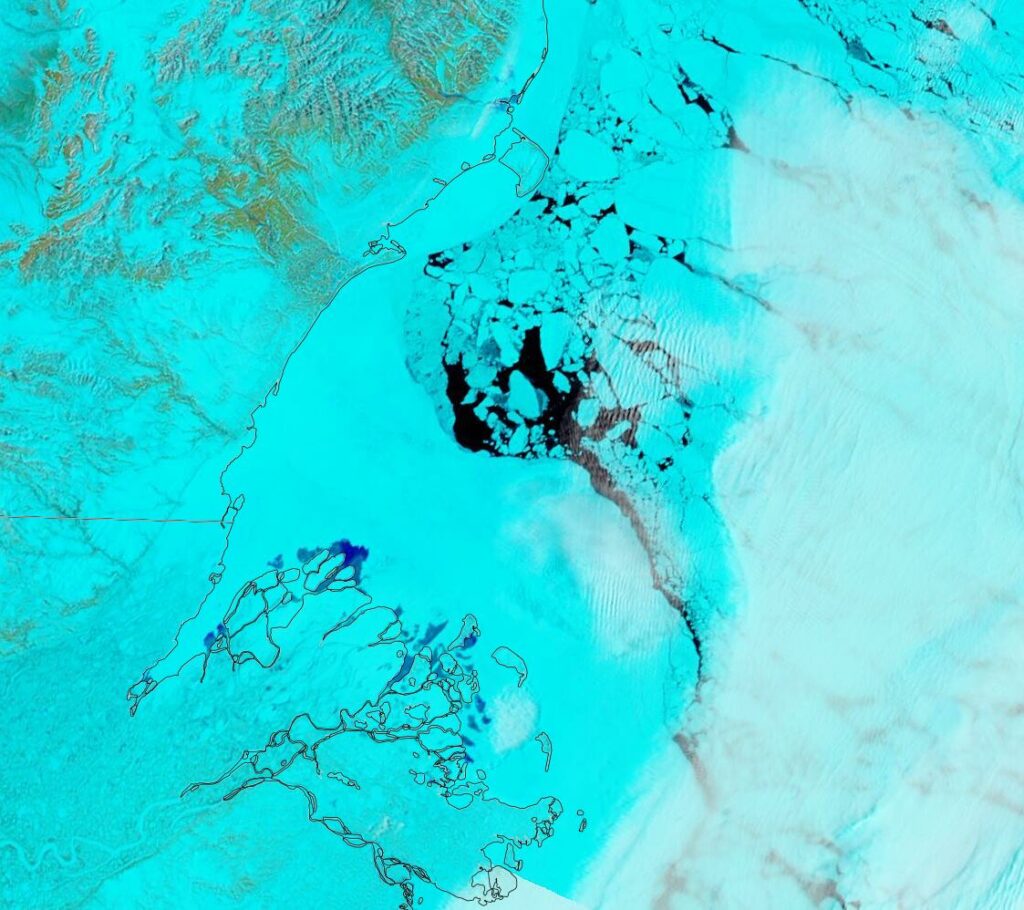

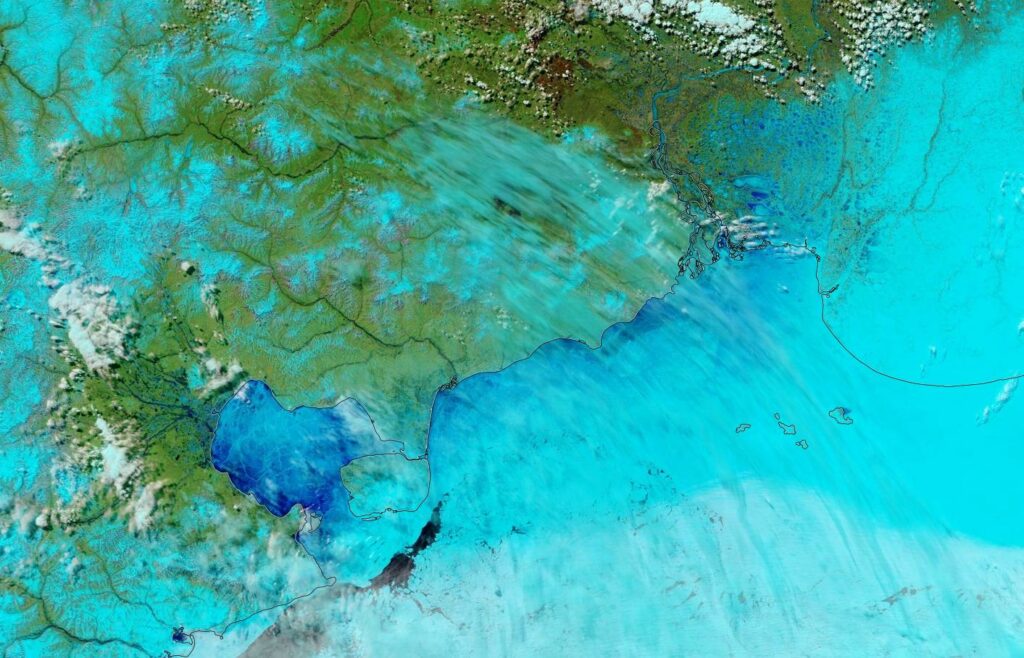

The NSIDC’s update also refers to the Chukchi Sea polynya we’ve been keeping an eye on here:

Strong offshore winds over the northwest coast of Alaska led to openings in the ice cover, called polynyas. The first pulse of winds began on March 21. At that time, surface air temperatures were still well below freezing, and the water in the coastal polynya quickly refroze. By April 9, the offshore push of the ice ceased and the polynya iced over completely.

However, starting on April 12, a second round of offshore wind pushed the ice away from the coast, initiating another polynya. Refreezing began anew in the open water areas, but the ice growth was noticeably slower, reflecting the higher surface air temperatures by the end of the month

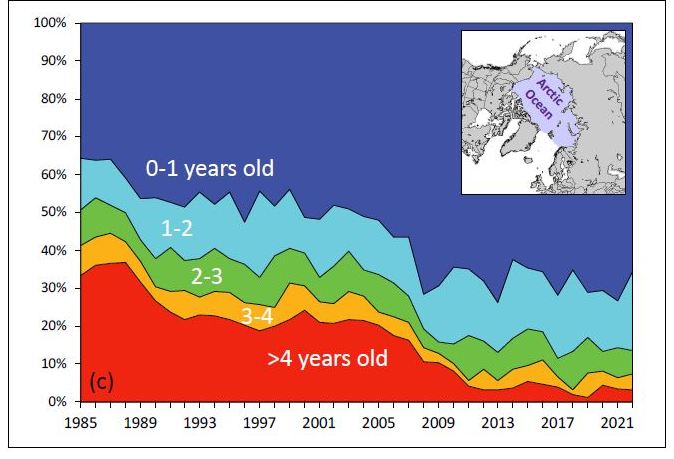

The NSIDC also updated their graph of sea ice age, on this occasion for the week of March 12th to 18th over the years:

Arctic sea ice news concludes with brief news of the recent death of Canadian Arctic scientist David Barber. CBC News’s obituary for David provides more details:

Family and friends are mourning the loss of the visionary Arctic researcher and University of Manitoba professor David Barber.

Barber, who was a distinguished professor, the founding director of the Centre for Earth Observation Science and associate dean of research in the faculty of environment, earth and resource, passed away on Friday after suffering complications from cardiac arrest.

Barber, 61, is survived by his wife Lucette, three children and two grandchildren.

The waters of the Mackenzie River are starting to spread over the fast ice off the delta:

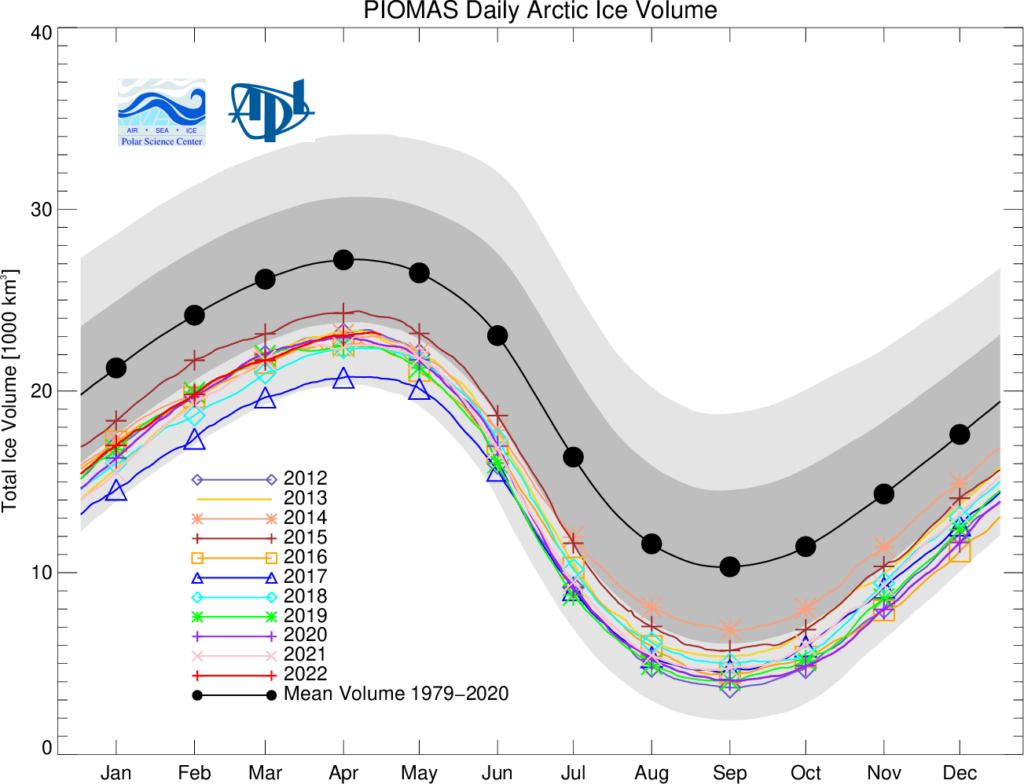

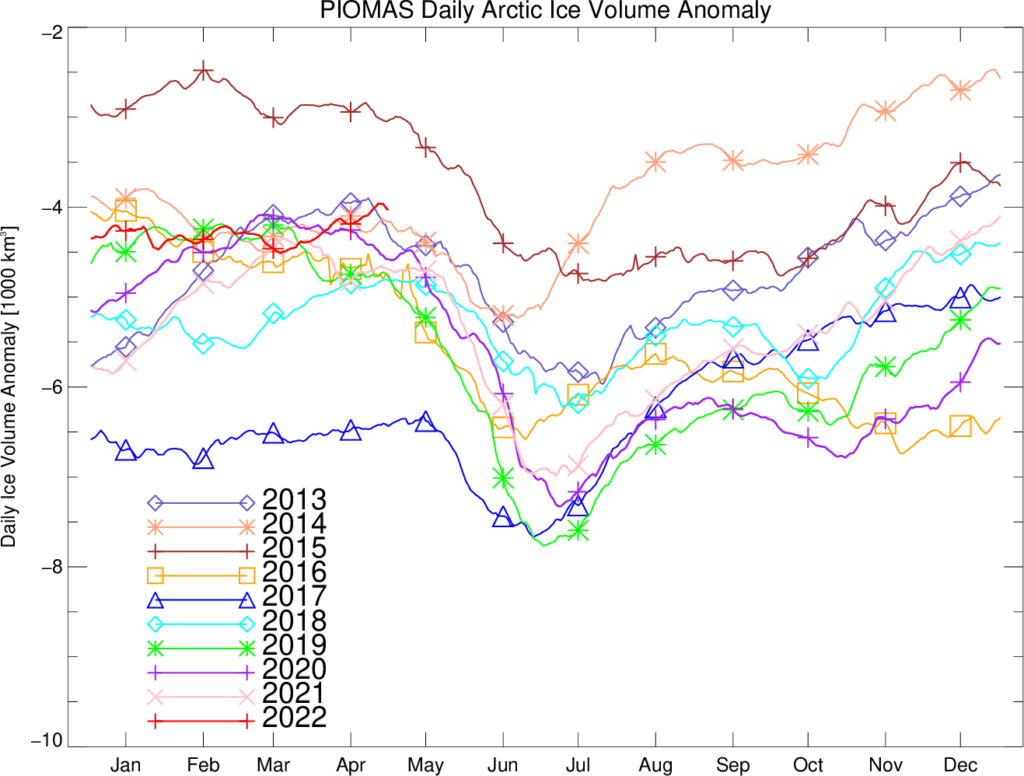

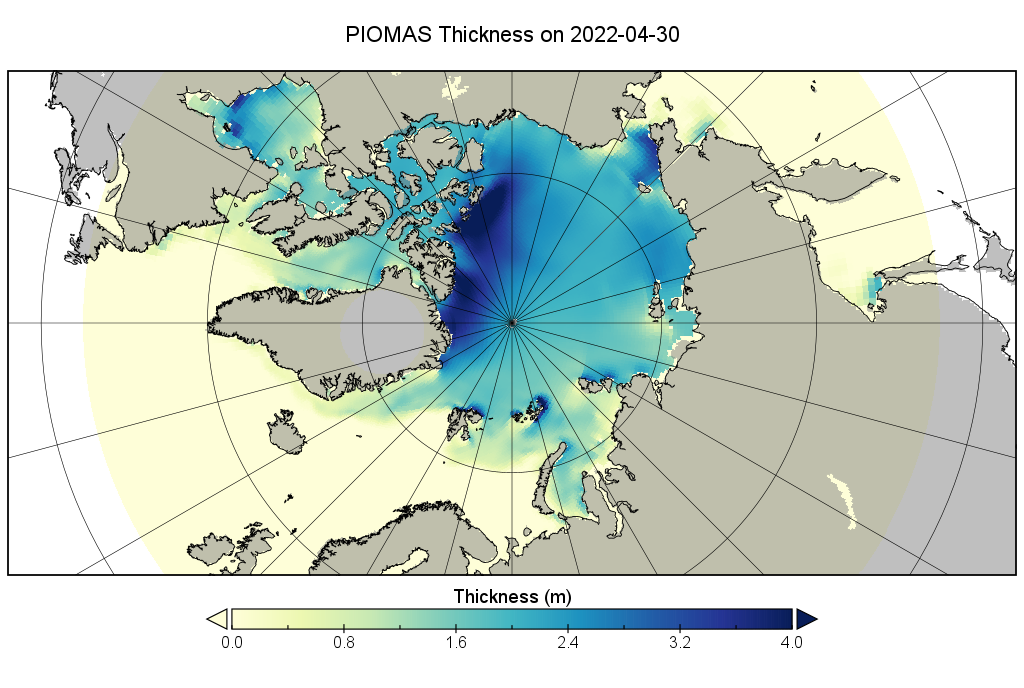

The Polar Science Center at the University of Washington has released the PIOMAS volume data for April 2022:

Average Arctic sea ice volume in April 2022 was 23,000 km3. This value is the 9th lowest on record for April, about 2,300 km3 above the record set in 2017. Monthly ice volume was 30% below the maximum in 1979 and 15% below the mean value for 1979-2021. Average April 2022 ice volume was 1.45 standard deviations above the 1979-2021 trend line.

The daily volume numbers reveal the PIOMAS maximum volume for 2022 to be 23,225 km3 on April 26th.

The PSC report continues:

Ice growth anomalies for April 2022 continued to be at the upper end of the most recent decade with a mean ice thickness (above 15 cm thickness) at the middle of recent values.

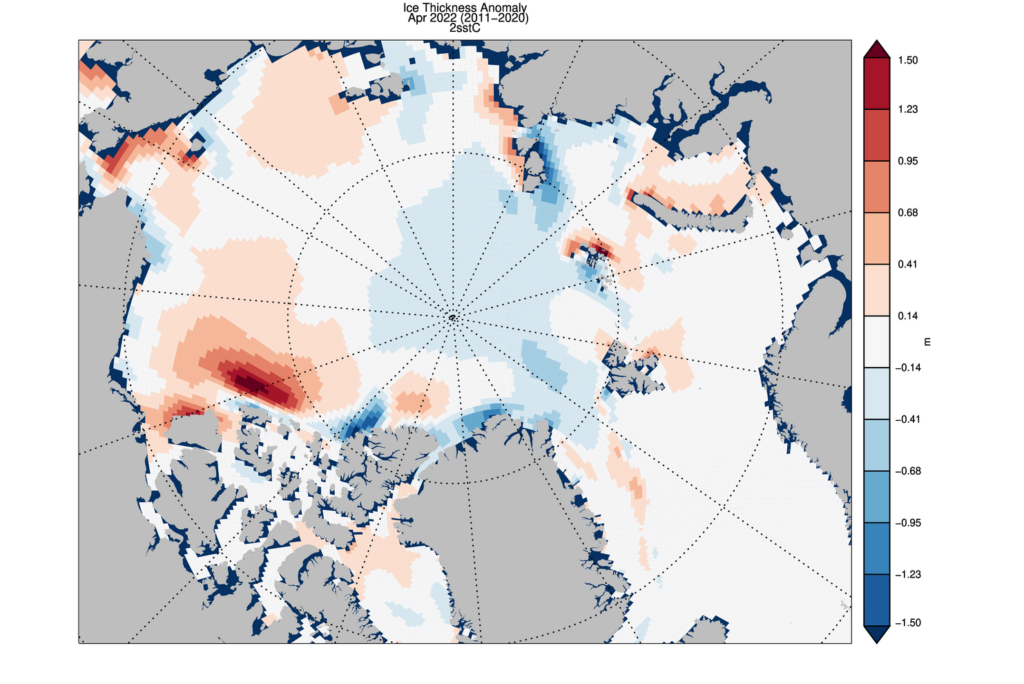

The ice thickness anomaly map for April 2022 relative to 2011-2020 divides the Arctic in two halves with positive anomalies in the “Western Arctic” but negative anomalies in “Eastern Arctic”. A narrow band of negative anomalies remains along the coast of North Greenland but a positive anomaly exists north of Baffin Island.

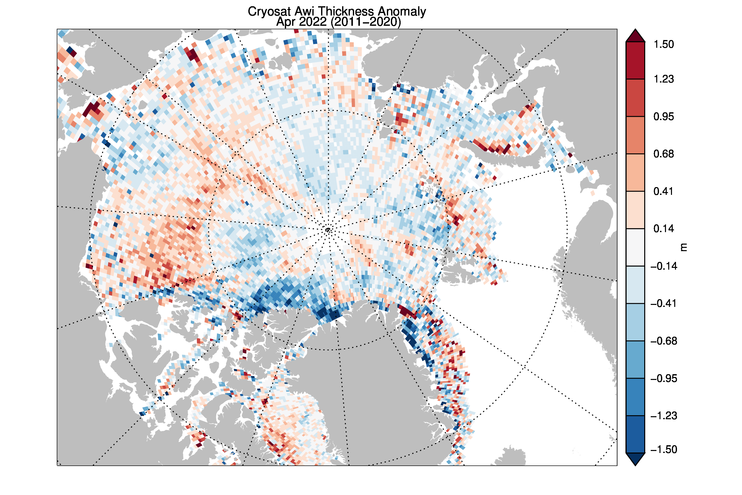

Note that the “positive anomaly north of Baffin Island” referred to is not apparent in the CryoSat 2 ice thickness anomaly map, although there is agreement about the thicker ice in the eastern Beaufort Sea:

CryoSat-2 thickness maps stopped for the Summer in mid April. I’ve been hoping for mid May data from the PIOMAS team, but in vain so far. In its continuing absence here is a “work in progress” PIOMAS thickness map for the end of April:

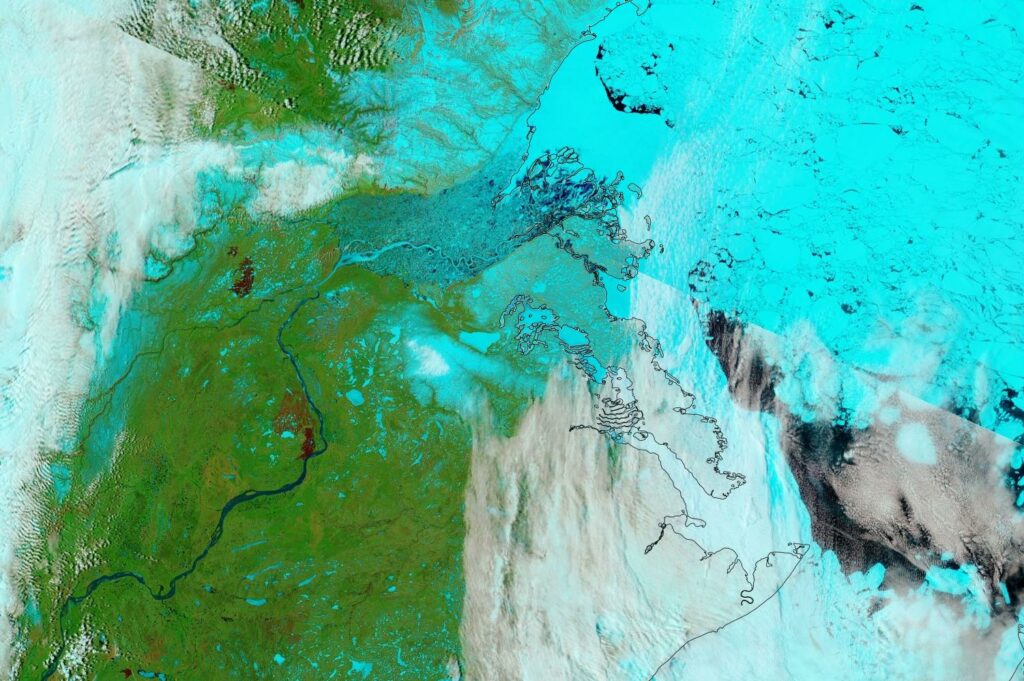

The sea ice in Chaunskaya Bay and along the adjacent coast of the East Siberian Sea is starting to look distinctly damp:

That’s not too surprising when you also look at recent temperatures in Pevek, which have been approaching all time highs for the date:

P.S. The Mackenzie River has reappeared from under the clouds and is now largely liquid:

Some surface melt is now visible on the fast ice at Utqiaġvik:

No doubt the recent above zero temperatures are responsible, but the forecast is for colder conditions to return:

Discussion continues on the new open thread for June 2022.